Variance, Covariance & Correlation

Hello. This statistics post will be an introduction on sample variances, sample covariances and sample correlations. These topics are typically found in an introductory course to probability and statistics.

No expected values will be shown here as there is more of a focus of sample data versus population data. (With that being said be mindful of the math notation.)

Review Of The Sample Mean

Recall that the formula for the sample mean of known data point values \(\bar{x}\) is \(\bar{x} = \displaystyle\dfrac{\Sigma_{i = 1}^{n} x_i}{n} = \dfrac{1}{n} (x_1 + x_2 + \dots + x_{n})\).

The sample mean is the equally weighted average of the data points and can be thought of as the center of the data. We use the sample mean \(\bar{x}\) to estimate (or make an informed guess about) the population mean \(\mu\). Remember that the sample data is a subset of the larger population. (E.g. A sample of 100, 000 Canadians from Canada)

Note

Means, medians, and modes are measures of central tendency which determine the most likely values given sample data. The terms variances, covariances and correlations are measures of variation. These measures of variation are useful in determining how random a random variable is.

When people say for example that the stock market is random, it is a vague statement as it does not specify any sort of quantity associated with the randomness of financial stocks (the range of values a financial stock can take on)

The Sample Variance

In the realm of probability and statistics, the variance can be thought of how far a set of (random) variables are from the mean.

The population variance is given by

\[\sigma^{2} = \displaystyle\dfrac{\Sigma_{i = 1}^{n} (X_i - \mu)^2}{n} = \dfrac{1}{n} [(X_1 - \mu)^2 + (X_2 - \mu)^2 + \dots + (X_{n} - \mu)^2)\].

We take the values of each \(X_i\), subtract it by the mean and square it. We then take the sum of these differenced squares and divide by \(n\).

This population variance is estimated by the sample variance (with known values). The sample variance is given by

\[s^2 = \displaystyle\dfrac{\Sigma_{i = 1}^{n} (x_i - \bar{x})^2}{n} = \dfrac{1}{n - 1} [(x_1 - \bar{x})^2 + (x_2 - \bar{x})^2 + \dots + (x_{n} - \bar{x})^2)\]

In the sample variance, we divide by (n - 1) which makes the sample variance an unbiased estimator of the population variance. In the long run or as the sample size \(n\) gets larger (approaching \(\infty\)), the sample variance would eventually reach (converge to) the population variance in theory.

Because of the exponent of 2, the variance is a non-negative value. It can be 0 or greater. If the variance is 0, that means that there is no randomness/variation on the random variable.

A Slight Note on Notation

If we have \(X_i\) then it is random and the value is unknown or unrealized. Once \(X_i\) is known or realized it is no longer random. Iit is now a known quantity and we use \(x_i\). Similarly, \(S^2\) is for the sample variance with unknown values but the sample variance \(s^2\) goes with known values and is no longer random.

Standard Deviation

The standard deviation is the square root of the variance and is used as a measure of how spread out the values of a sample data are. If one knows about z-scores, the standard deviation is the number of z-scores from the mean. The variance being non-negative (0 or positive) ensures that the number inside the square root is positive.

The standard deviation for a population is \(\sqrt{\sigma^2} = \sigma\).

The sample standard deviation (of known values) is \(\sqrt{s^2} = s\).

Sample Covariances

The covariance is a varability measure of how two random variables change together. If the covariance is positve for random variables \(X\) and \(Y\) (as an example) then as X increases in numeric value then Y increases as well. For the negative covariance case, as X increases in numeric value then Y decreases in value.

The sample covariance (with known values) is:

\[s_{xy} = \displaystyle\dfrac{\Sigma_{i = 1}^{n} (x_i - \bar{x})(y_i - \bar{y})}{n} = \dfrac{1}{n - 1} [ (x_1 - \bar{x})(y_1 - \bar{y}) + (x_2 - \bar{x})(y_2 - \bar{y})+ \dots + (x_n - \bar{x})(y_n - \bar{y}))\]

where \(\bar{x}\) is the sample mean associated with X and \(\bar{y}\) is the sample mean associated with Y.

If \(y = x\) then we have \(s_{xx}\) or \(s_{yy}\) which is in the same form as \(s^2\) from earlier. Do keep in mind that \(s_{xx}\) goes with the \(x_{i}\)s and \(s_{yy}\) goes with the \(y_{i}\)s.

Sample Correlations

Correlation is not much different than covariance. Correlation is a variability measure which measures the relationship between two random variables (or sets of data). The sample correlation formula is as follows:

\[r_{xy} = \dfrac{s_{xy}}{\sqrt{s_{xx} \text{ }s_{yy} }}\]

The numerator is the covariance and the denominator is the square root of the sample variance with the \(x_{i}\)s multiplied by the sample variance with \(y_{i}\)s . Correlations can be viewed as scaled versions of covariances.

Notes

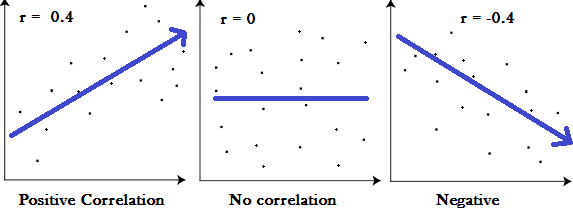

Correlations are between -1 to 1.

A positive correlation between random variables \(X\) and \(Y\) means that as \(X\) increases then \(Y\) increases as well. With the negative correlation case, as \(X\) increases then \(Y\) decreases.

Correlations close to zero suggest that the two variables have no relation with each other.

A correlation close to -1 suggests a very strong relationship where as \(X\) increases then \(Y\) decreases. A correlation of +1 suggests a very strong relationship where as \(X\) increases then \(Y\) increases.

Correlation measures of about 0.5 or -0.5 suggest a moderate correlation and values closer to 0 suggest a weak association between two random variables.

The table image below is one aid to help associate correlation measures with relationship strengths between two (random) variables. (Other tables would have other definitions of moderate/strong/weak correlation strengths.)

Link: http://www.statisticshowto.com/probability-and-statistics/correlation-coefficient-formula/

Correlation Does Not Imply Causation

The most important thing you should remember when it comes to correlations is that “Correlation does not mean causation!”. Correlations measure the relationship and dependence between two variables based on a sample from the population. The sample size \(n\) may not be “large” relative to the population size. Also, there may be other variables which could affect the dependent variable \(Y\).

The take home message is that just because \(X\) appears to cause \(Y\), it doesn’t mean it actually does (as we don’t have all the data/information). There could be other variables (known and unknown) relate to the variable \(Y\).

Reference

- Casella, G. and Berger R.L. (2002), Statistical Inference, 2nd Edition, Duxbury