Understanding Logarithmic Functions

This article will be about logarithmic functions. This particular concept is typically taught in pre-calculus/calculus courses. I also made a post about logarithms here.

A Short Review of Exponential Functions

An exponential function is a function of the form:

\[\displaystyle a^{x}\]

where \(a\) is a non-zero number and \(x\) is a variable.

When we are given \(2^4\) we know that it is \(2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 = 16\). But what if we have to find the exponent \(a\) such that \(5^a = 26\)? We know that \(5^2 =25\) and \(5^3 = 125\) but we do not know for sure (without a calculator). It is not ideal to guess and test values as it is better to be precise. This is where logarithms come in.

The Logarithmic Function

The logarithmic function is the inverse function of the exponential function and is of the form:

\[\displaystyle \log_a (x)\]

where the base \(a\) is a non-zero number and \(x\) is a variable.

Given the base of the exponential, a known answer and an unknown exponent, the logarithm helps us find the unknown exponent.

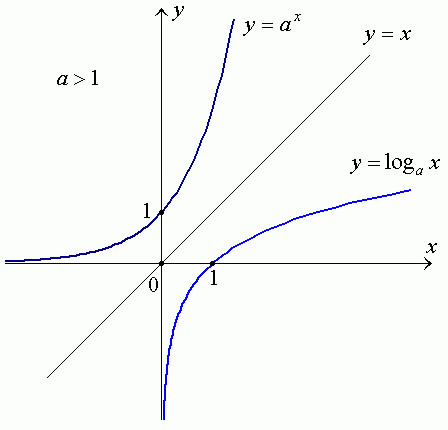

The picture below illustrates how the exponential and the logarithmic functions are inverse functions of each other. They are both mirror images of each other where the middle is the y = x line.

A Memory Aid

In a more easy to understand manner the relation between exponential functions and logarithmic functions is like this:

[Exponential Function] \(base^{exponent} = answer\)

[Logarithmic Function] \(\log_{base}(answer) = exponent\)

A more simpler memory aid would be to use the first letter:

[Exponential Function] \(b^{e} = a\)

[Logarithmic Function] \(\log_{b}(a) = e\)

You could use a memory aid such bea and bae or ebea and lbae to help you. Note that this e is not Euler’s constant of \(e \approx 2.71828\). One could use the letter p for power instead of e for exponent.

Domain and Range of Logarithmic Functions

Recall that with the exponential function has a domain of \(x \in (-\infty, +\infty)\) and a range of \(\text{e}^{x} \in (0, +\infty)\). That is, \(x\) can take on any real number and \(\text{e}^{x}\) is non-negative or at least zero.

Since the logarithmic function is the inverse of the exponential function, the domain and range would be reversed for the logarithmic function. That is, the domain of the logarithmic function is \(x \in (0, +\infty)\) (all positive numbers for \(x\)) and \(\text{log}(x) \in (- \infty, +\infty)\)

Properties of Logarithmic Functions

Here are some properties of the logarithm function:

\[\displaystyle \log_{a}(x \cdot y) = \log_{a}(x) + \log_{a}(y)\]

\[\displaystyle \log_{a}(x / y) = \log_{a}(x) - \log_{a}(y)\]

\[\displaystyle \log_{a}(x^{b}) = b \cdot \log_{a}(x)\]

\[\displaystyle \log_{a}(1) = 0\]

\[\displaystyle \log_{a}(a) = 1\]

\[\displaystyle \lim_{x \rightarrow +\infty} \log_{a}(x) = +\infty\]

\[\displaystyle \lim_{x \rightarrow 0^{+}} \log_{a}(x) = -\infty\]

The Change of Base Formula

The common bases for logarithms are base e, base 10 (and base 2 for some areas of mathematics). What if we want to evaluate logs for non-common bases? The change of base formula comes in handy. It allows us to evaluate logarithms with non-common bases using logarithms with known bases. Logarithms with known bases are calculator-friendly.

\[\displaystyle \log_{b}(x) = \dfrac{\log_{c}(x)}{\log_{c}(b)}\]

Alternatively, one could use natural logarithms or ln(x) in the change of base formula.

\[\displaystyle \log_{b}(x) = \dfrac{\text{ln}(x)}{\text{ln}(b)}\]

Examples

To put the theory into practice, here are some examples.

Example One

If \(100 = 10^{x}\), what is \(x\)?

Taking the logarithms (of base 10) of both sides of the equation and solving for \(x\) gives us:

\[\displaystyle \begin{array} {lcl} 100 & = & 10^{x} \\ \log_{10}(100) & = & \log_{10}(10^{x})\\ 2 & = & x \cdot \log_{10}(10)\\ 2 & = & x \cdot 1\\ x & = & 2 \\ \end{array} \]

Example Two

If \(8 = e^{2x}\), what is \(x\)?

Here we take logarithms of base e of both sides of the equation.

\[\displaystyle \begin{array} {lcl} 8 & = & e^{2x} \\ \text{ln}(8) & = & \text{ln}(e^{2x})\\ \text{ln}(8) & = & 2x \cdot \text{ln}(e)\\ 2.0794 & \approx & 2x \cdot 1\\ \dfrac{2.0794}{2} & \approx & x\\ x & \approx & 1.0397 \\ \end{array} \\ \]

Example Three

Evaluate \(\text{log}_{5}(e^3)\) using the change of base formula.

Answer:

\[\displaystyle \begin{array} {lcl} \log_{5}(e^3) & = & \dfrac{\text{ln}(e^3)}{\text{ln}(5)} \\ \log_{5}(e^3) & = & \dfrac{3}{\text{ln}(5)} \\ \log_{5}(e^3) & \approx & \dfrac{3}{1.6094} \\ \log_{5}(e^3) & \approx & 1.8640 \\ \end{array} \\ \]

Example Four

Evaluate the binary logarithm \(\log_{2}(25)\).

Answer:

\[\displaystyle \begin{array} {lcl} \log_{2}(25) & = & \dfrac{\text{ln}(25)}{\text{ln}(2)} \\ \log_{2}(25) & \approx & \dfrac{3.2189}{0.6931} \\ \log_{2}(25) & \approx & 4.6442\\\end{array} \\ \]