The Bisection Method

Hi there. This page is about the bisection method for finding approximate roots or x-intercepts to polynomial equations.

What Is The Bisection Method?

The Bisection method aims to find approximate solutions to polynomial equations with the use of midpoints. It also belongs to a class of numerical methods. Numerical methods provide approaches to certain mathematical problems when finding the exact numeric answers is not possible. Instead of finding exact answers, we find approximate solutions with a certain loss of precision. Some approximate answers are close to the real answer by 0.01 and some are as close as \(10^{-6}\).

The Intermediate Value Theorem

To help us understand the bisection method, I think it is important to go over the Intermediate Value Theorem (IVT) from calculus.

Suppose there is a continuous function \(f(x)\) in a closed interval \([a, b]\) with \(f(a)\) and \(f(b)\). Then there is some number \(c\) such that we have \(a \leq c \leq b\) and \(min(f(a), f(b)) \leq f(c) \leq max(f(a), f(b))\). This \(f(c)\) would be a horizontal line \(k\) or even 0.

Note that I have put in the min and max parts above to deal with both increasing and decreasing functions. If \(f(x)\) is an increasing function in the interval \([a, b]\) then I have \(f(a) \leq f(c) \leq f(b)\). With the other case I would have \(f(a) \geq f(c) \geq f(b)\) if \(f(x)\) is an decreasing function in the interval \([a, b]\).

Source: http://www.vitutor.com/calculus/limits/images/0_301.gif

In the bisection method, we try to look for the number \(c\) such that \(f(c) = 0\).

The Algorithm

Here is a rough idea of what the bisection method function would look like in a programming language such as R, Python, etc. At each interation, we want to shrink the interval [a, b].

# Pseudocode For Bisection Method

if f(a)*f(b) > 0

print("No root found") # Both f(a) and f(b) are the same sign

else

while (b - a) / 2 > tolerance

c = (b + a) /2 # c is like a midpoint

if f(c) == 0

return(midpt) # The midpt is the root such that f(midpt) = 0

else if f(a)*f(c) < 0

b = c # Shrink interval from right.

else

a = c

return(c)

In \(f(a)f(c) < 0\), either is \(f(a)\) is negative or \(f(c)\) is negative. If \(f(a)\) is positive then the line has to cross the x-axis to get to \(f(c)\) which is megative. In this case, the new \(b\) would be \(c\). In the increasing case, \(f(a)\) would be negative and \(f(c)\) would be positive. The choice here would be having the new \(b\) as \(c\).

With the \(f(a)f(c) > 0\) case, you would choose the new \(a\) as \(c\).

This process is repeated until (b - a)/2 is small enough (or the interval is very small).

Picture Example

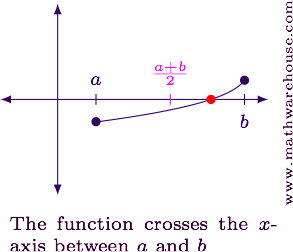

Source: http://www.mathwarehouse.com/calculus/continuity/images/bisection-algorithm-basic-idea.png

Suppose \(c = \dfrac{a + b}{2}\) and the function is increasing.In this case, f(c) is negative, f(a) is negative and f(b) is positive. You would not choose c as the new b since both f(c) and f(a) are negative and there would be no root in the interval [a, c]. Instead, you choose \(c\) as the new \(a\) to obtain the new subinterval as [c, b].