A Guide To Dot Products

This post is an introduction to dot products. It is assumed that the reader knows about vectors where a vector in \(\mathbb{R}^{n}\) is of the form \(\textbf{v} = (v_1, v_2, \dots, v_{n})\). In addition, the reader should be familiar with the concept of a norm.

Definition of the Dot Product

The dot product or the Euclidean inner product is an algebraic operation which takes two vectors of the same length and returns a scalar number. Think of the dot product as another operation like +, - , \(\times\) and \(\div\).

Given the vectors \(\textbf{u} = (u_1, u_2, \dots, u_{n})\) and \(\textbf{v} = (v_1, v_2, \dots, v_{n})\) in \(\mathbb{R}^{n}\), the dot product of \(\textbf{u}\) and \(\textbf{v}\) denoted by \(\textbf{u} \cdot \textbf{v}\) is:

\[ \textbf{u} \cdot \textbf{v} = \sum_{j=1}^{n} u_j v_j = u_1 v_1 + u_2v_2 + \dots + u_n v_n\]

If we have the special case of \(\textbf{u} \cdot \textbf{u}\) then we obtain the square of the norm as follows:

\[\begin{array} {lcl} \textbf{u} \cdot \textbf{u} & = & \sum_{j=1}^{n} u_j u_j \\ & = & u_1 u_1 + u_2u_2 + \dots + u_n u_n\\ & = & (u_1)^2 + (u_2)^2 + \dots + (u_n)^2\\ & = & ||\textbf{u}||^2 \\ \end{array}\]

From the above result, we can identify that the norm or the length of a vector \(\textbf{u}\) can be expressed as the square root of the dot product (below).

\[||\textbf{u}||= \sqrt{\textbf{u} \cdot \textbf{u}}\]

Properties

When introduced with a new operation, some properties need to be introduced. These may not sound exciting but they are important. Think of it like grammar in languages.

Suppose we have vectors \(\textbf{u}\), \(\textbf{v}\) and \(\textbf{w}\) in \(\mathbb{R}^{n}\) and \(k\) as a scalar (real number), we have these properties.

[Symmetry Property]

\[ \textbf{u} \cdot \textbf{v} = \textbf{v} \cdot \textbf{u}\]

[Distributive Property]

\[\textbf{u} \cdot (\textbf{v} + \textbf{w}) = \textbf{u} \cdot \textbf{v} + \textbf{v} \cdot \textbf{w} \]

[Homogeneity Property]

\[ k (\textbf{u} \cdot \textbf{v}) = (k \textbf{u}) \cdot \textbf{v}\]

[Positivity Property]

\[ \textbf{v} \cdot \textbf{v} \geq 0 \text{ and } \textbf{v} \cdot \textbf{v} = 0 \text{ if and only if } \textbf{v} = 0\]

The above four properties look scary but they are not too bad. Here are a couple of more below:

\[ \textbf{0} \cdot \textbf{v} = \textbf{v} \cdot \textbf{0}= \textbf{0}\].

\[ (\textbf{u} + \textbf{v}) \cdot \textbf{w} = \textbf{u} \cdot \textbf{w} + \textbf{v} \cdot \textbf{w} \]

\[ \textbf{u} \cdot (\textbf{v} - \textbf{w}) = \textbf{u} \cdot \textbf{v} - \textbf{u} \cdot \textbf{w} \]

\[ (\textbf{u} - \textbf{v}) \cdot \textbf{w} = \textbf{u} \cdot \textbf{w} - \textbf{v} \cdot \textbf{w} \]

\[k(\textbf{u} \cdot \textbf{v}) = \textbf{u} \cdot (k\textbf{v})\]

Geometry and Dot Products

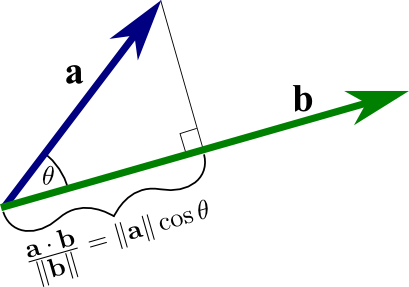

Dot products along with norms can help us find the cosine of an angle \(\theta\). A useful formula is:

\[\cos(\theta) = \dfrac{\textbf{u} \cdot \textbf{v}}{||\textbf{u}|| ||\textbf{v}||}\]

where \(\textbf{u}\), \(\textbf{v}\) are vectors in \(\mathbb{R}^{n}\) and \(\theta\) is the angle between \(\textbf{u}\) and \(\textbf{v}\). The angle \(\theta\) is defined to be between 0 and \(\pi\) (\(0 \leq \theta \leq \pi\) in radians or 0 to 90 degrees).

We can find out some out some information about \(\theta\) based on the dot product.

If \(\textbf{u} \cdot\textbf{v} > 0\) then \(\theta\) is an acute angle (0 to less than 90 degrees).

If \(\textbf{u} \cdot\textbf{v} < 0\) then \(\theta\) is an obtuse angle (More than 90 degrees to less than 180 degrees).

If \(\textbf{u} \cdot\textbf{v} = 0\) then \(\theta\) is a right angle (\(\theta\) = 90 degrees or \(\dfrac{\pi}{2}\)).

The visual aid below helps with visualizing how the dot product operates.

Link Source: http://thejuniverse.org/PUBLIC/LinearAlgebra/LOLA/dotProd/def.html

Examples

Example One

The dot product of vectors \(\textbf{a} = (1, -2)\) and \(\textbf{b} = (-10, -3)\) is:

\[\begin{array} {lcl} \textbf{a} \cdot \textbf{b} & = & 1 \cdot (-10) + (-2) \cdot (-3) \\ & = & -10 + 6 \\ & = & -4 \\ \end{array}\]

Example Two

Given vectors \(\textbf{a} = (1, -2, 5, 3)\) and \(\textbf{b} = (4, -3, -7, 2)\), the dot product of these vectors in \(\mathbb{R}^{4}\) is:

\[\begin{array} {lcl} \textbf{a} \cdot \textbf{b} & = & 1 \cdot 4 + (-2) \cdot (-3) + 5 \cdot (-7) + 3 \cdot 2 \\ & = & 4 + 6 - 35 + 6\\ & = & -19 \\ \end{array} \]

Example Three

Suppose we are given the vectors \(\textbf{a} = (3, -5)\), \(\textbf{b} = (-1, 4)\) and \(\textbf{c} = (3, 2)\). What is \((\textbf{a} + \textbf{c}) \cdot \textbf{b}\)

Answer:

We compute \((\textbf{a} + \textbf{c})\) first then take the dot product of \((\textbf{a} + \textbf{c})\) with .

\[\begin{array} {lcl} (\textbf{a} + \textbf{c}) \cdot \textbf{b} & = & (3 + 3, -5 + 2) \cdot (-1, 4) \\ & = & (6, -3) \cdot (-1, 4) \\ & = & 6 \cdot (-1) + (-3) \cdot 4\\ & = & -6 - 12\\ & = & -18\\ \end{array} \]

Example Four

Simplify (2\(\textbf{u}\) - \(\textbf{v}\)) \(\cdot\) (\(\textbf{u}\) + 3\(\textbf{v}\)).

Answer:

In this scenario, we do not know the elements of \(\textbf{u}\) or \(\textbf{v}\) nor do we know the dimensionality of these vectors in \(\mathbb{R}^{n}\). It could be in \(\mathbb{R}^{4}\), \(\mathbb{R}^{2}\) or even \(\mathbb{R}^{1000}\). All we can do is simplify as follows.

\[\begin{array} {lcl} (2 \textbf{u} - \textbf{v}) \cdot (\textbf{u} + 3\textbf{v}) & = & 2 \textbf{u} \cdot (\textbf{u} + 3\textbf{v}) - \textbf{v} \cdot (\textbf{u} + 3\textbf{v})\\ & = & 2 (\textbf{u} \cdot \textbf{u}) + 6 (\textbf{u} \cdot \textbf{v}) - (\textbf{v} \cdot \textbf{u}) - 3 (\textbf{v}\cdot \textbf{v}) \\ & = & 2 ||\textbf{u}||^2 + 6 (\textbf{u} \cdot \textbf{v}) - (\textbf{u} \cdot \textbf{v}) - 3||\textbf{v}||^2 \\ & = & 2 ||\textbf{u}||^2 + 5 (\textbf{u} \cdot \textbf{v}) - 3||\textbf{v}||^2 \\ \end{array}\]

This particular question used a lot of properties of dot products and norms. One may want to reread this particular question for better understanding.

There are more properties and formulas related to the dot product such as the Cauchy-Schwarz Inequality, the Parallelogram for two vectors, dot products with \(\cos(\theta)\), and dot products as matrix multiplication. Those won’t be mentioned here.