What Is Compound Interest (Part 2/2)

Hello. This page is a follow up from the What Is Compound Interest (Part 1/2) page. There is more math and theory in this lengthy post. One may want to skip right to the tips and notes section for more practical advice.

Remember that one should invest and handle their own funds at their own risk!

The pictures below are from my camera phone and my Wipebook.

The featured image is from http://www.comefaretradingonline.com/images/guadagnare-col-trading.jpg

Table Of Contents

- Introduction

- Compound Interest Periods

- Equivalent Interest Rates

- Time Value of Money, Present Value and Future Value

- Examples

- Tips and Notes

Introduction

In the previous post, the interest rate was compounded annually or once a year. Note that all interest rates are not the same in the sense they may be compounded multiple times a year. (Interest rates can differ in numerical value too!) We also take a look at semi-annual compounding, quarterly compounding, monthly compounding, and continuous compounding.

Recall that we started out with the idea that $1 today is not the same as $1 from 10 years ago nor 10 years from now (due to inflation, deflation, currency rates, etc).

Compound Interest Periods

As before, it is assumed that the funds/monies are to be reinvested or left in the account without withdrawals.

In the previous post, the annually compounded interested rate was used. This annual interest rate lasts for 12 months. Alternatively, we can say that the interest period is 12 months.

If we have a semi-compounded interest rate then we have 2 periods of 6 months each per year. Each interest rate period lasts for six months.

For the quarterly compounded interest rate (compounded 4 times a year) then we have 4 periods of 3 months each per year. Each interest rate period lasts for three months.

For the interest rate being compounded monthly (compounded 12 times a year) then we have 12 periods of 1 month each per year. Each interest rate period lasts for one month.

If we have the interest rate being compounded weekly (or 52 times a year) then we have 52 periods of 1 week each per year. Each interest rate period lasts for one week.

Also, some interest rates are compounded daily.

Accumulated Value

The accumulated value of $1 at the end of \(m\) interest periods for \(n\) years is:

\[\displaystyle \begin{array}{lr} \displaystyle (1 + \dfrac{i^{(m)}}{m})^{mn} \end{array} \]

where \(i^{(m)}\) is the nominal interest rate which is compounded \(m\) times per year.

(For example \(i^{(12)} = 12\%\) means a nominal interest rate of 12% compounded monthly or 12 times a year.)

With the case of continuous compounding where the interest is compounded infinitely, the accumulated value of $1 at the end of \(n\) years is \(e^{rt}\) where \(r\) is the fixed annual interest rate and \(t\) is the number of years. The proof follows from deriving Euler’s constant e in Calculus.

Equivalent Interest Rates

We now look at equivalent interest rates. For example a 5% interest rate compounded annually and a 5% interest rate compounded semi annually are not the same. Likewise, a 7% interest compounded quarterly and a 5% interest rate compounded semi annually are not the same.

To go from an interest rate to another interest rate (with different compounding) we set up this equation:

\[\displaystyle \begin{array}{lcl} (1 + \dfrac{i^{(m)}}{m})^{m} & = & (1 + \dfrac{i^{(n)}}{n})^{n} \end{array} \]

where \(i^{(m)}\) and \(i^{(n)}\) are different interest rates and \(m \neq n\).

Suppose we know a certain interest rate such as \(i^{(m)}\) compounded \(m\) times for example and want to know \(i^{(n)}\) with \(n\) compounding periods. The above formula (algebraically rearranged) can help finding an equivalent interest rate \(i^{(n)}\) or \(i^{(m)}\).

Annual Effective Rate

Suppose we want to know the annual effective rate \(i^{(1)} = i\) from other interest rates. We use a variation or special case of the above equation setup as follows:

\[\displaystyle \begin{array}{lcl} (1 + i) & = & (1 + \dfrac{i^{(n)}}{n})^{n} \end{array}\]

Through rearrangement the interest rate \(i\) is just \(i = (1 + \dfrac{i^{(n)}}{n})^{n} - 1\) for the annual year. For the continuous compounded interest rate case we have \(i = \text{e}^{n} - 1.\)

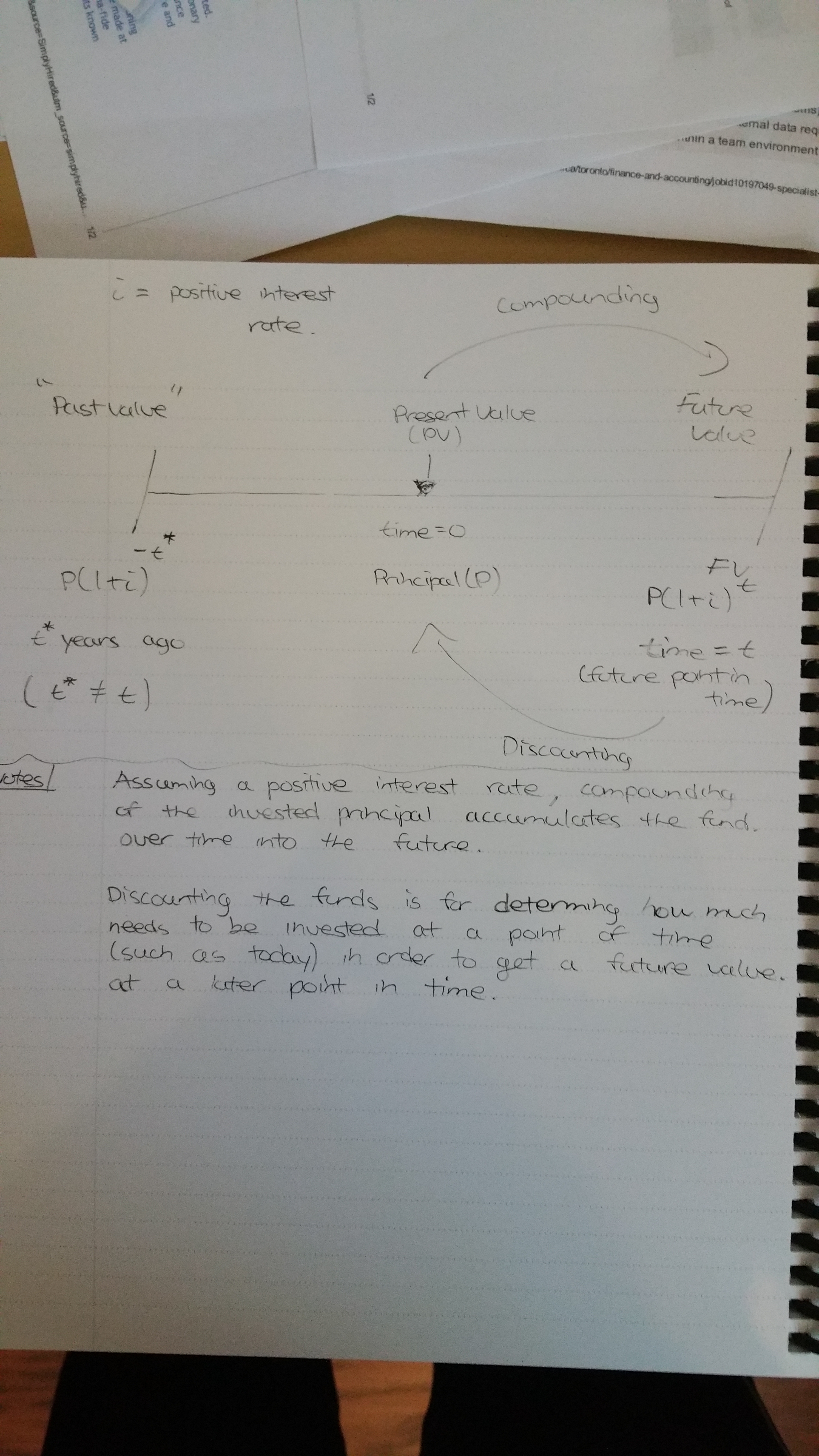

Time Value of Money, Present Value and Future Value of Money

We now look at the time value of money. Recall that $1 today does not have the same value as $1 in the future nor it is the same $1 in the past due to inflation, deflation or randomly changing currency exchange rates over time.

To illustrate the concept of time value of money we assume a constant or fixed positive interest rate \(i\) or \(i^{(m)}\) and an amount \(P\) today (time \(t=0\)).

The future (or final) value \(F\) of the invested amount \(P\) at time \(t = mn\) (from now) would be:

\[\displaystyle \begin{array}{lcl} \displaystyle F & = & P \cdot(1 + \dfrac{i^{(m)}}{m})^{mn} \end{array}\]

(m for number of compounding periods and n number of years)

This future value is larger than \(P\) as the growth rate \((1 + \dfrac{i^{(m)}}{m})\) is larger than 1.

Suppose we wanted to know how much money to invest into a savings account today in order to have a future amount \(F\) \(t\) years (\(t = mn\)) from now. Instead of multiplying the growth rate, we divide by the growth rate.

\[\displaystyle \begin{array}{lcl} \displaystyle P & = & F \cdot (1 + \dfrac{i^{(m)}}{m})^{-(mn)} \end{array} \]

The image below summarizes the time value of money, present value and future value concepts.

Examples

These examples are not necessarily real life examples! They are for illustrating concepts and to give you a good idea on how interest rates work.

1) Example One (RESP Savings)

Suppose that a family (in Canada) would like to start a Registered Education Savings Plan (RESP) to start saving money for their child’s education. They would like invest their money as a one time plan through a lump sum payment.

The lump sum payment after fees (principal) is \(P = \$ 8100\). The time horizon is 15 years with a fixed semi-annually compounded interest rate of \(i^{(2)} = 3\%\) per annum.

The calculations of the future value of the savings after 15 years is as follows:

\[\displaystyle \begin{array}{lcl} FV & = & \$ 8100 \cdot (1 + \dfrac{0.03}{2})^{2 \cdot 15}\\ & = & \$8100 \cdot (1 + 0.015)^{30} \\ & = & \$ 12,660.95 \end{array} \]

2) Example Two (RESP Savings with a different lump sum and time horizon)

Assuming the same interest rate as in example one above, suppose the principal is now \(P = \$ 7400\) and the time horizon is 17 years. The calculations would be:

\[\displaystyle \begin{array}{lcl} FV & = & \$7400 \cdot (1 + \dfrac{0.03}{2})^{2 \cdot 17}\\ & = & \$7400\cdot (1 + 0.015)^{34} \\ & = & \$12,276.57 \end{array} \]

As you can clearly see, increasing the time horizon and/or increasing the (invested) principal amount (exponentially) increases the funds over time.

3) Example Three (Continuous Compounded Interest)

If we were to use a continuously compounded interest in the examples above, the calculations would not be that much different. The calculations would be as follows:

\[\displaystyle \begin{array}{lcl} FV & = & \$8,100\text{e}^{0.03 \cdot 15}\\ & = & \$8,100\text{e}^{0.45}\\ & = & \$12,703.33 \end{array} \]

\[\displaystyle \begin{array}{lcl} FV & = & \$ 7,400\text{e}^{0.03 \cdot 17}\\ & = & \$ 7,400\text{e}^{0.51}\\ & = & \$ 12,323.15 \end{array} \]

All else equal, using the continuous compounded rate over the semi-annually compounded interest rate yields slightly more money in the savings.

4) Example Four (Paying Back a Loan)

Suppose we currently have a loan of $21, 500 from 5 years ago. Up to now, no (partial) payments have been made to reduce this loan amount. The daily interest is 3.78% per annum. What is the loan amount now?

\[\displaystyle \begin{array}{lcl} FV & = & \$21,500 \cdot (1 + \dfrac{0.0378}{365})^{5 \cdot 365}\\ & = & \$21,500 \cdot (1.000048767)^{1825} \\ & = & \$25,972.63 \end{array} \]

5) Example Five (Finding Out Original Loan)

Here is a slightly more involved example. Suppose that we now know that we owe $7,890 in loans right now. We want to know what was the original loan amount 2 years ago. No payments were made to reduce the loan amount and we assume a fixed interest rate of 4% semi-annually. Note that payments are annual. What was the original loan amount?

First we switch from a semi-annual interest rate to an annual interest rate to match the annual payment structure of the loan. We use the annual effective rate formula as such:

\[\displaystyle \begin{array}{lcl} i^{(1)}& = & (1 + \dfrac{i^{(2)}}{2})^{2} - 1 \\ & = & (1 + \dfrac{0.04}{2})^{2} - 1 \\ & = & (1.02)^{2} - 1 \\ & = & 0.0404 \\ & = & 4.04\% \\ \end{array} \]

We now use this new 4.04% to discount the known $7,890 amount to find the original loan amount from 2 years ago (with annual payments).

\[\displaystyle \begin{array}{lcl} P & = & \$ 7,890 \cdot (1 + \dfrac{0.0404}{1})^{- 2 \cdot 1}\\ & = & \$ 7,890 \cdot (1.0404)^{-2} \\ & = & \$ 7,289.14 \end{array} \].

The original loan amount from two years ago was $7,289.14 at a 4% semi-annual interest rate with annual payments (which were not made). A summary picture is below.

Tips and Notes

Saving early is a good idea. That way, the compound interest will work well over time. However, this assumes you have enough income to put aside for a savings account.

When it comes to borrowing and loans. It is important to try to pay back loans as soon as possible. If loans are not paid off over time then compound interest can work against you (snowball effect). That $1000 loan can turn into $10,000 with all the accumulated interest over time.

We do not assume multiple principal payments. That would be more for annuities, another payment method where it deals with regular payments (every month/year/time period).

Be aware of fees. We assumed no fees nor deductions.

We assumed that interest rates are fixed or non-random (for simplicity mostly). Dealing with variable/random interest rates is much, much harder. Be aware.

Different financial products will carry various interest rates with different compounding frequencies. For example, an annual interest rate of 5% is not the same as 5% interest compounded daily.

Reference: Financial Mathematics: A Comprehensive Treatment by Giuseppe Campolieti and Roman N. Makarov